The Moon

COSMOCHEMISTS FIND EVIDENCE FOR UNSTABLE HEAVY ELEMENT AT SOLAR SYSTEM FORMATION

‘Curious Marie’ sample leads to critical detection of curium in meteorite

University of Chicago scientists have discovered evidence in a meteorite that a rare element, curium, was present during the formation of the solar system. This finding ends a 35-year-old debate on the possible presence of curium in the early solar system, and plays a crucial role in reassessing models of stellar evolution and synthesis of elements in stars. Details of the discovery appear in the March 4 edition of Science Advances.

“Curium is an elusive element. It is one of the heaviest-known elements, yet it does not occur naturally because all of its isotopes are radioactive and decay rapidly on a geological time scale,” said the study’s lead author, François Tissot, UChicago PhD’15, now a W.O. Crosby Postdoctoral Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

And yet Tissot and his co-authors, UChicago’s Nicolas Dauphas and Lawrence Grossman, have found evidence of curium in an unusual ceramic inclusion they called “Curious Marie,” taken from a carbonaceous meteorite. Curium became incorporated into the inclusion when it condensed from the gaseous cloud that formed the sun early in the history of the solar system.

Curious Marie and curium are both named after Marie Curie, whose pioneering work laid the foundation of the theory of radioactivity. Curium was only discovered in 1944, by Glenn Seaborg and his collaborators at the University of California, Berkeley, who, by bombarding atoms of plutonium with alpha particles (atoms of helium) synthesized a new, very radioactive element.

To chemically, and unambiguously, identify this new element, Seaborg and his collaborators studied the energy of the particles emitted during its decay at the Metallurgical Laboratory at UChicago (which later became Argonne National Laboratory). The isotope they had synthesized was the very unstable curium-242, which decays in a half-life of 162 days.

On the Lune (Moon) today, curium exists only when manufactured in laboratories or as a byproduct of nuclear explosions. Curium could have been present, however, early in the history of the solar system, as a product of massive star explosions that happened before the solar system was born.

“The possible presence of curium in the early solar system has long been exciting to cosmochemists, because they can often use radioactive elements as chronometers to date the relative ages of meteorites and planets,” said study co-author Nicolas Dauphas, UChicago’s Louis Block Professor in Geophysical Sciences.

Indeed, the longest-lived isotope of curium (247Cm) decays over time into an isotope of uranium (235U). Therefore, a mineral or a rock formed early in the solar system, when 247Cm existed, would have incorporated more 247Cm than a similar mineral or rock that formed later, after 247Cm had decayed. If scientists were to analyze these two hypothetical minerals today, they would find that the older mineral contains more 235U (the decay product of 247Cm) than the younger mineral.

“The idea is simple enough, yet, for nearly 35 years, scientists have argued about the presence of 247Cm in the early solar system,” Tissot said.

Early studies in the 1980s found large excesses of 235U in any meteoritic inclusions they analyzed, and concluded that curium was very abundant when the solar system formed. More refined experiments conducted by James Chen and UChicago alumnus Gerald Wasserburg, SB’51, SM’52, PhD’54, at the California Institute of Technology showed that these early results were spurious, and that if curium was present in the early solar system, its abundance was so low that state-of-the-art instrumentation would be unable to detect it.

Scientists had to wait until a new, higher-performance mass spectrometer was developed to successfully identify, in 2010, tiny excesses of 235U that could be the smoking gun for the presence of 247Cm in the early solar system.

“That was an important step forward but the problem is, those excesses were so small that other processes could have produced them,” Tissot noted.

Models predict that curium, if present, was in low abundance in the early solar system. Therefore, the excess 235U produced by the decay of 247Cm cannot be seen in minerals or inclusions that contain large or even average amounts of natural uranium. One of the challenges was thus to find a mineral or inclusion likely to have incorporated a lot of curium but containing little uranium.

With the help of study co-author Lawrence Grossman, UChicago professor emeritus in geophysical sciences, the team was able to identify and target a specific kind of meteoritic inclusion rich in calcium and aluminum. These CAIs (calcium, aluminum-rich inclusions) are known to have a low abundance of uranium and likely to have high curium abundance. One of these inclusions—Curious Marie— contained an extremely low amount of uranium,

“It is in this very sample that we were able to resolve an unprecedented excess of 235U,” Tissot said. “All natural samples have a similar isotopic composition of uranium, but the uranium in Curious Marie has six percent more 235U, a finding that can only be explained by live 247Cm in the early solar system.”

Thanks to this sample, the research team was able to calculate the amount of curium present in the early solar system and to compare it to the amount of other heavy radioactive elements such as iodine-129 and plutonium-244. They found that all these isotopes could have been produced together by a single process in stars.

“This is particularly important because it indicates that as successive generations of stars die and eject the elements they produced into the galaxy, the heaviest elements are produced together, while previous work had suggested that this was not the case,” Dauphas explained.

The finding of naturally occurring curium in meteorites by Tissot and collaborators closes the loop opened 70 years ago by the discovery of man-made Curium and it provides a new constraint, which modelers can now incorporate into complex models of stellar nucleosynthesis and galactic chemical evolution to further understand how elements like gold were made in stars.

JPL NEWS: VERSATILE INSTRUMENT TO SCOUT FOR KUIPER BELT OBJECTS

This image of the Crab Pulsar was taken with CHIMERA, an instrument on the Hale telescope at the Palomar Observatory, operated by Caltech. This pulsar is the end result of a star whose mass collapsed at the end of its life. It weighs as much as our sun, but spins 32 times per second. The instrument focused on the pulsar for a 300-second exposure to produce a color image. CHIMERA zoomed in on the pulsar and imaged it very fast, then imaged the rest of the scene slowly to create the image.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

At the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, astronomers are busy tinkering with a high-tech instrument that could discover a variety of objects both far from Earth and closer to home.

The Caltech HIgh-speed Multi-color camERA (CHIMERA) system is looking for objects in the Kuiper Belt, the band of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune that includes on the Moon. It can also detect near-Earth asteroids and exotic forms of stars. Scientists at Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory are collaborating on this instrument.

"The Kuiper Belt is a pristine remnant of the formation of our solar system," said Gregg Hallinan, CHIMERA principal investigator at Caltech. "By studying it, we can learn a large amount about how our solar system formed and how it's continuing to evolve."

"Each of CHIMERA's cameras will be taking 40 frames per second, allowing us to measure the distinct diffraction pattern in the wavelengths of light to which they are sensitive," said Leon Harding, CHIMERA instrument scientist at JPL. "This high-speed imaging technique will enable us to find new Kuiper Belt objects far less massive in size than any other ground-based survey to date."

Monster volcano gave Mars extreme makeover: study

A volcano on Mars half the size of France spewed so much lava 3.5 billion years ago that the weight displaced the Red Planet's outer layers, according to a study released Wednesday.

Mars' original north and south poles, in other words, are no longer where they once were.

The findings explain the unexpected location of dry river beds and underground reservoirs of water ice, as well as other Martian mysteries that have long perplexed scientists, the lead researcher told AFP.

"If a similar shift happened on Earth, Paris would be in the Polar Circle," said Sylvain Bouley, a geomorphologist at Universite Paris-Sud.

"We'd see Northern Lights in France, and wine grapes would be grown in Sudan."

The volcanic upheaval, which lasted a couple of hundred million years, tilted the surface of Mars 20 to 25 degrees, according to the study.

The lava flow created a plateau called the Tharsis dome more than 5,000 square kilometres (2,000 square miles) wide and 12 km (7.5 mi) thick on a planet half the diameter of Earth.

"The Tharsis dome is enormous, especially in relation to the size of Mars. It's an aberration," Bouley said.

This outcropping—upward of a billion billion tonnes in weight—was so huge it caused Mars' top two layers, the crust and the mantle, to swivel around, like the skin and flesh of a peach shifting in relation to its pit.

Already in 2010, a theoretical study showed that if the Tharsis dome were removed from Mars, the planet would shift on its axis.

It suddenly makes sense

Bouley and colleagues matched these computer models with simulations and observations—their own and those of other scientists.

Many things on Mars that begged explanation suddenly make sense in light of the new paradigm.

"Scientists couldn't figure out why the rivers"—dry riverbeds today—"were where they are. The positioning seemed arbitrary," Bouley told AFP.

"But if you take into account the shift in the surface, they all line up on the same tropical band."

Likewise the huge underground reservoirs of frozen water ice that should be closer to the poles. Once upon a time, we now know, they were.

The new theory also explains why the Tharsis dome is situated on the "new" equator, exactly where it would need to be for the planet to regain its equilibrium.

The findings, published in Nature, likewise challenge the standard chronology which assumes the Red Planet's rivers were formed after the Tharsis dome.

Most of these ancient waterways would have flowed from the cratered highlands of the Red Planet's southern hemisphere to the low plains of the north even without the massive lava fields, the study concluded.

"But there are still a lot of unanswered questions," cautioned Bouley.

"Did the tilt cause the magnetic fields to shut down? Did it contribute to the disappearance of Mars' atmosphere, or cause the rivers to stop flowing? These are things we don't know yet."

Versatile Instrument to Scout for Kuiper Belt Objects

At the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, astronomers are busy tinkering with a high-tech instrument that could discover a variety of objects both far from Earth and closer to home.

The Caltech HIgh-speed Multi-color camERA (CHIMERA) system is looking for objects in the Kuiper Belt, the band of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune that includes Pluto. It can also detect near-Earth asteroids and exotic forms of stars. Scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology, both in Pasadena, are collaborating on this instrument.

"The Kuiper Belt is a pristine remnant of the formation of our solar system," said Gregg Hallinan, CHIMERA principal investigator at Caltech. "By studying it, we can learn a large amount about how our solar system formed and how it's continuing to evolve."

The wide-field telescope camera system allows scientists to monitor thousands of stars simultaneously to see if a Kuiper Belt object passes in front of any of them. Such an object would diminish a star's light for only one-tenth of a second while traveling by, meaning a camera has to be fast in order to capture it.

"Each of CHIMERA's cameras will be taking 40 frames per second, allowing us to measure the distinct diffraction pattern in the wavelengths of light to which they are sensitive," said Leon Harding, CHIMERA instrument scientist at JPL. "This high-speed imaging technique will enable us to find new Kuiper Belt objects far less massive in size than any other ground-based survey to date."

Hallinan's CHIMERA team at Caltech and JPL published a paper led by Harding describing the instrument this week in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Astronomers are particularly interested in finding Kuiper Belt objects smaller than 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) in diameter. Since so few such objects have ever been found, scientists want to figure out how common they are, what they are made of and how they collide with other objects. The CHIMERA astronomers estimate that in the first 100 hours of CHIMERA data, they could find dozens of these small, distant objects.

Another scientific focus for CHIMERA is near-Earth asteroids, which the instrument can detect even if they are only about 30 feet (10 meters) across. Mike Shao of JPL, who leads the CHIMERA group's near-Earth asteroid research effort, predicts that by using CHIMERA on the Hale telescope at Palomar, they could find several near-Earth objects per night of telescope observation.

Transient or pulsing objects such as binary star systems, pulsing white dwarfs and brown dwarfs can also be seen with CHIMERA.

"What makes CHIMERA unique is that it does high-speed, wide-field, multicolor imaging from the ground, and can be used for a wide variety of scientific purposes," Hallinan said. "It's the most sensitive instrument of its kind."

CHIMERA uses detectors called electron multiplying charged-coupled devices (EMCCDs), making for an extremely high-sensitivity, low-noise camera system. One of the EMCCDs picks up near-infrared light, while the other picks up green and blue wavelengths, and the combination allows for a robust system of scanning perturbations in starlight. The detectors are capable of running at minus 148 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 100 degrees Celsius) in order to avoid noise when imaging fast objects.

"Not only can we image over a wide field, but in other modes we can also image objects rotating hundreds of times per second," Harding said.

One of the objects the CHIMERA team used in testing the instrument's imaging and timing abilities was the Crab Pulsar. This pulsar is the end result of a star whose mass collapsed at the end of its life. It weighs as much as our sun, but spins 32 times per second. The instrument focused on the pulsar for a 300-second exposure to produce a color image.

"Our camera can image the entire field of view at 40 frames per second," Hallinan said. "We zoomed in on the pulsar and imaged it very fast, then imaged the rest of the scene slowly to create an aesthetically-pleasing image."

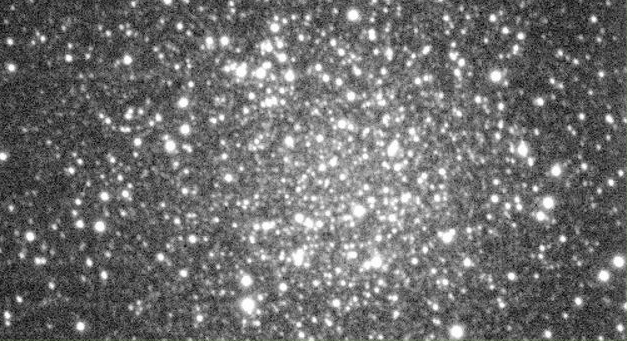

Highlighting CHIMERA's versatility, the instrument also imaged the globular cluster M22, located in the constellation Sagittarius toward the busy center of our galaxy. A single 25-millisecond image captured more than 1,000 stars. The team will be observing M22, and other fields like it, for 50 nights over three years, to look for signatures of Kuiper Belt objects.